<texit info> author=Ivan Savov title=Mechanics backgroundtext=off </texit>

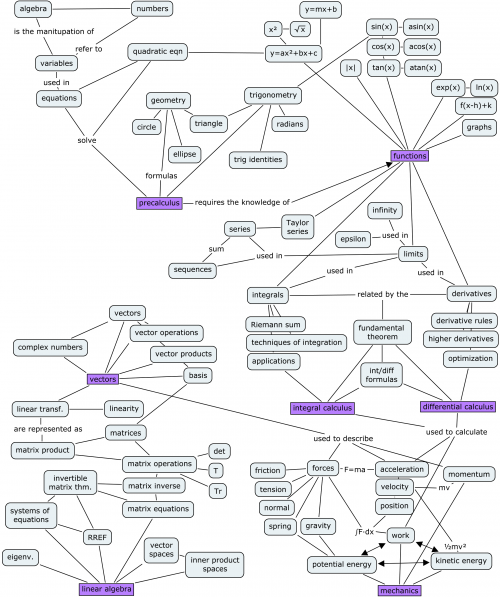

Front matter

About

This book contains short lessons on topics in math and physics. The coverage of each topic is at the depth required for a university-level course written in a style that is short and to the point. A motivated reader can easily learn enough calculus and mechanics from this book to get an A on the final exam on these subjects. You can learn everything you need to know in two weeks, then you will need another week to practice exercises. Three weeks and you are done.

Calculus and mechanics can be difficult subjects, but they become easy when you break down the concepts into manageable chunks. The most important thing is to learn about the connections between concepts and to understand what is going on intuitively. Every time you learn about some new concept, you need to connect it with all your previous knowledge.

Speaking of previous knowledge...

In order to get off on the right foot, the book begins with a comprehensive review of math fundamentals like algebra, equation solving and functions. Anyone can pick up this book and become proficient in calculus and mechanics regardless of their mathematical background. You can skip the first chapter if you feel comfortable with high school math concepts, though it might still be a good idea for you to do a flyover for review purposes.

Why?

The genesis of this book dates back to my days as an undergraduate student when I was forced to purchase expensive textbooks that were required for my courses. Not only are these textbooks expensive, but they are also long and tedious to read. The standard introductory physics textbook is 1040 pages long and the calculus book is another 1311 pages. I can tell you for a fact that you don't need to read 2300 pages to learn math and physics and calculus, so what is the deal? The reason why mainstream textbooks are so big is that this allows the textbook publishers to suck more money out of you. You wouldn't pay 150 dollars for a 300 page textbook now would you? The fact that a new edition of the textbook comes out every couple of years with almost no changes to the content shows that textbook publishers are not really out to teach you stuff, but only after your money.

Looking at this situation, I said to myself “Something must be done!” and I sat down to write a modern textbook that explains things clearly and concisely. The book you have in your hands.

How?

Each section in this book is like a self-contained private tutorial. Indeed, the lessons you will read grew from my experience as a private tutor. The writing is chill and conversational, but we keep a quick pace through the material. Prerequisites topics are introduced as needed. There are a lot of hands-on explanations through solved examples. We cover the same material as the 400 page textbook in just 40 pages. I call this process information distillation.

Who?

Since this is an “about” section, I will say something about me.

I have been tutoring math and physics privately for more than ten years.

I did my undergraduate studies at McGill University in Electrical Engineering,

then I did a M.Sc. in Physics and I recently completed a Ph.D. in Computer Science.

I have been developing this book in parallel with my studies and,

on the day of my graduation, I founded the Minireference Publishing Co.

revolutionize the textbook industry.

This is the deal. You give me 250 pages of your attention, and I will teach you everything I know about functions, limits, derivatives, integrals, vectors, forces and accelerations. The book which you hold in your hands is the only book you need for the first year of undergraduate studies in science.

Mathematics fundamentals

In this chapter we will review the fundamental ideas of mathematics like numbers, equations and functions. In order to understand college-level textbooks you need to be comfortable with mathematical calculations.

Solving equations

Most math skills boil down to being able to manipulate and solve equations. To solve an equation means to find the value of the unknown in the equation.

Check this shit out: \[ x^2-4=45. \]

To solve the above equation is to answer the question “What is $x$?” More precisely, we want to find the number which can take the place of $x$ in the equation so that the equality holds. In other words, we are asking \[ \text{"Which number times itself minus four gives 45?"} \]

That is quite a mouthful don't you think? To remedy this verbosity, mathematicians often use specialized mathematical symbols. The problem is that the specialized symbols used by mathematicians are confuse people. Sometimes even the simplest concepts are inaccessible if you don't know what the symbols mean.

What are your feelings about math, dear reader? Are you afraid of it? Do you have anxiety attacks because you think it will be too difficult for you? Chill! Relax my brothers and sisters. There is nothing to it. Nobody can magically guess what the solution is immediately. You have to break the problem down into simpler steps.

To find $x$, we can manipulate the original equation until we transform it to a different equation (as true as the first) that looks like this: \[ x= just \ some \ numbers. \]

That's what it means to solve. The equation is solved because you could type the numbers on the right hand side of the equation into a calculator and get the exact value of $x$.

To get $x$, all you have to do is make the right manipulations on the original equation to get it to the final form. The only requirement is that the manipulations you make transform one true equation into another true equation.

Before we continue our discussion, let us take the time to clarify what the equality symbol $=$ means. It means that all that is to the left of $=$ is equal to all that is to the right of $=$. To keep this equality statement true, you have to do everything that you want to do to the left side also to the right side.

In our example from earlier, the first simplifying step will be to add the number four to both sides of the equation: \[ x^2-4 +4 =45 +4, \] which simplifies to \[ x^2 =49. \] You must agree that the expression looks simpler now. How did I know to do this operation? I was trying to “undo” the effects of the operation $-4$. We undo an operation by applying its inverse. In the case where the operation is subtraction of some amount, the inverse operation is the addition of the same amount.

Now we are getting closer to our goal, namely to isolate $x$ on one side of the equation and have just numbers on the other side. What is the next step? Well if you know about functions and their inverses, then you would know that the inverse of $x^2$ ($x$ squared) is to take the square root $\sqrt{ }$ like this: \[ \sqrt{x^2} = \sqrt{49}. \] Notice that I applied the inverse operation on both sides of the equation. If we don't do the same thing on both sides we would be breaking the equality!

We are done now, since we have isolated $x$ with just numbers on the other side: \[ x = \pm 7. \]

What is up with the $\pm$ symbol? It means that both $x=7$ and $x=-7$ satisfy the above equation. Seven squared is 49, and so is $(-7)^2 = 49$ because two negatives cancel out.

If you feel comfortable with the notions of high school math and you could have solved the equation $x^2-4=25$ on your own, then you should consider skipping ahead to Chapter 2. If on the other hand you are wondering how the squiggle killed the power two, then this chapter is for you! In the next sections we will review all the essential concepts from high school math which you will need for the rest of the book. First let me tell you about the different kinds of numbers.

Functions and their inverses

As we saw in the section on solving equations, the ability to “undo” functions is a key skill to have when solving equations.

Example

Suppose you have to solve for $x$ in the equation \[ f(x) = c. \] where $f$ is some function and $c$ is some constant. Our goal is to isolate $x$ on one side of the equation but there is the function $f$ standing in our way.

The way to get rid of $f$ is to apply the inverse function (denoted $f^{-1}$) which will “undo” the effects of $f$. We find that: \[ f^{-1}\!\left( f(x) \right) = x = f^{-1}\left( c \right). \] By definition the inverse function $f^{-1}$ does the opposite of what the function $f$ does so together they cancel each other out. We have $f^{-1}(f(x))=x$ for any number $x$.

Provided everything is kosher (the function $f^{-1}$ must be defined for the input $c$), the manipulation we made above was valid and we have obtained the answer $x=f^{-1}( c)$.

\[ \ \]

Note the new notation for denoting the function inverse $f^{-1}$ that we introduced in the above example. This notation is borrowed from the notion of “inverse number”. Multiplication by the number $d^{-1}$ is the inverse operation of multiplication by the number $d$: $d^{-1}dx=1x=x$. In the case of functions, however, the negative one exponent does not mean the inverse number $\frac{1}{f(x)}=(f(x))^{-1}$ but functions inverse, i.e., the number $f^{-1}(y)$ is equal to the number $x$ such that $f(x)=y$.

You have to be careful because sometimes the applying the inverse leads to multiple solutions. For example, the function $f(x)=x^2$ maps two input values ($x$ and $-x$) to the same output value $x^2=f(x)=f(-x)$. The inverse function of $f(x)=x^2$ is $f^{-1}(x)=\sqrt{x}$, but both $x=+\sqrt{c}$ and $x=-\sqrt{c}$ would be solutions to the equation $x^2=c$. A shorthand notation to indicate the solutions for this equation is $x=\pm c$.

Formulas

Here is a list of common functions and their inverses:

\[ \begin{align*} \textrm{function } f(x) & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \textrm{inverse } f^{-1}(x) \nl x+2 & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ x-2 \nl 2x & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \frac{1}{2}x \nl -x & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ -x \nl x^2 & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \pm\sqrt{x} \nl 2^x & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \log_{2}(x) \nl 3x+5 & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \frac{1}{3}(x-5) \nl a^x & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \log_a(x) \nl \exp(x)=e^x & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \ln(x)=\log_e(x) \nl \sin(x) & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \arcsin(x)=\sin^{-1}(x) \nl \cos(x) & \ \Leftrightarrow \ \ \arccos(x)=\cos^{-1}(x) \end{align*} \]

The function-inverse relationship is reflexive. This means that if you see a function on one side of the above table (no matter which), then its inverse is on the opposite side.

Example

Let's say your teacher doesn't like you and right away on the first day of classes, he gives you a serious equation and wants you to find $x$: \[ \log_5\left(3 + \sqrt{6\sqrt{x}-7} \right) = 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1). \] Do you see now what I meant when I said that the teacher doesn't like you?

First note that it doesn't matter what $\Psi$ is, since $x$ is on the other side of the equation. We can just keep copying $\Psi(1)$ from line to line and throw the ball back to the teacher in the end: “My answer is in terms of your variables dude. You have to figure out what the hell $\Psi$ is since you brought it up in the first place.” The same goes with $\sin(5.5)$. If you don't have a calculator, don't worry about it. We will just keep the expression $\sin(5.5)$ instead of trying to find its numerical value. In general, you should try to work with variables as much as possible and leave the numerical computations for the last step.

OK, enough beating about the bush. Let's just find $x$ and get it over with! On the right side of the equation, we have the sum of a bunch of terms and no $x$ in them so we will just leave them as they are. On the left-hand side, the outer most function is a logarithm base $5$. Cool. No problem. Looking in the table of inverse functions we find that the exponential function is the inverse of the logarithm: $a^x \Leftrightarrow \log_a(x)$. To get rid of the $\log_5$ we must apply the exponential function base five to both sides: \[ 5^{ \log_5\left(3 + \sqrt{6\sqrt{x}-7} \right) } = 5^{ 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1) }, \] which simplifies to: \[ 3 + \sqrt{6\sqrt{x}-7} = 5^{ 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1) }, \] since $5^x$ canceled the $\log_5 x$.

From here on it is going to be like if Bruce Lee walked into a place with lots of bad guys. Addition of $3$ is undone by subtracting $3$ on both sides: \[ \sqrt{6\sqrt{x}-7} = 5^{ 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1) } - 3. \] To undo a square root you take the square \[ 6\sqrt{x}-7 = \left(5^{ 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1) } - 3\right)^2. \] Add $7$ to both sides \[ 6\sqrt{x} = \left(5^{ 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1) } - 3\right)^2+7. \] Divide by $6$: \[ \sqrt{x} = \frac{1}{6}\left(\left(5^{ 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1) } - 3\right)^2+7\right), \] and then we square again to get the final answer: \[ \begin{align*} x &= \left[\frac{1}{6}\left(\left(5^{ 34+\sin(5.5)-\Psi(1) } - 3\right)^2+7\right) \right]^2. \end{align*} \]

Did you see what I was doing in each step? Next time a function stands in your way, hit it with its inverse, so that it knows not to ever challenge you again.

Discussion

The recipe I have outlined above is not universal. Sometimes $x$ isn't alone on one side. Sometimes $x$ appears in several places in the same equation so can't just work your way towards $x$ as shown above. You need other techniques for solving equations like that.

The bad news is that there is no general formula for solving complicated equations. The good news is that the above technique of “digging towards $x$” is sufficient for 80% of what you are going to be doing. You can get another 15% if you learn how to solve the quadratic equation: \[ ax^2 +bx + c = 0. \]

Solving third order equations $ax^3+bx^2+cx+d=0$ with pen and paper is also possible, but at this point you really might as well start using a computer to solve for the unknown(s).

There are all kinds of other equations which you can learn how to solve: equations with multiple variables, equations with logarithms, equations with exponentials, and equations with trigonometric functions. The principle of digging towards the unknown and applying the function inverse is very important so be sure to practice it.

Solving quadratic equations

What would you do if you were asked to find $x$ in the equation $x^2 = 45x + 23$? This is called a quadratic equation since it contains the unknown variable $x$ squared. The name name comes from the Latin quadratus, which means square. Quadratic equations come up very often so mathematicians came up with a general formula for solving these equations. We will learn about this formula in this section.

Before we can apply the formula, we need to rewrite the equation in the form \[ ax^2 + bx + c = 0, \] where we moved all the numbers and $x$s to one side and left only $0$ on the other side. This is the called the standard form of the quadratic equation. For example, to get the expression $x^2 = 45x + 23$ into the standard form, we can subtract $45x+23$ from both sides of the equation to obtain $x^2 - 45x - 23 = 0$. What are the values of $x$ that satisfy this formula?

Claim

The solutions to the equation \[ ax^2 + bx + c = 0, \] are \[ x_1 = \frac{-b + \sqrt{b^2-4ac} }{2a} \ \ \text{ and } \ \ x_2 = \frac{-b - \sqrt{b^2-4ac} }{2a}. \]

Let us now see how this formula is used to solve the equation $x^2 - 45x - 23 = 0$. Finding the two solutions is a simple mechanical task of identifying $a$, $b$ and $c$ and plugging these numbers into the formula: \[ x_1 = \frac{45 + \sqrt{45^2-4(1)(-23)} }{2} = 45.5054\ldots, \] \[ x_2 = \frac{45 - \sqrt{45^2-4(1)(-23)} }{2} = -0.5054\ldots. \]

Proof of claim

This is an important proof. You should know how to derive the quadratic formula in case your younger brother asks you one day to derive the formula from first principles. To derive this formula, we will use the completing-the-square technique which we saw in the previous section. Don't bail out on me now, the proof is only two pages.

Starting from the equation $ax^2 + bx + c = 0$, our first step will be to move $c$ to the other side of the equation \[ ax^2 + bx = -c, \] and then to divide by $a$ on both sides \[ x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x = -\frac{c}{a}. \]

Now we must complete the square on the left-hand side, which is to say we ask the question: what are the values of $h$ and $k$ for this equation to hold \[ (x-h)^2 + k = x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x = -\frac{c}{a}? \] To find the values for $h$ and $k$, we will expand the left-hand side to obtain $(x-h)^2 + k= x^2 -2hx +h^2+k$. We can now identify $h$ by looking at the coefficients in front of $x$ on both sides of the equation. We have $-2h=\frac{b}{a}$ and hence $h=-\frac{b}{2a}$.

So what do we have so far: \[ \left(x + \frac{b}{2a} \right)^2 = \left(x + \frac{b}{2a} \right)\!\!\left(x + \frac{b}{2a} \right) = x^2 + \frac{b}{2a}x + x\frac{b}{2a} + \frac{b^2}{4a^2} = x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x + \frac{b^2}{4a^2}. \] If we want to figure out what $k$ is, we just have to move that last term to the other side: \[ \left(x + \frac{b}{2a} \right)^2 - \frac{b^2}{4a^2} = x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x. \]

We can now continue with the proof where we left off \[ x^2 + \frac{b}{a}x = -\frac{c}{a}. \] We replace the left-hand side by the complete-the-square expression and obtain \[ \left(x + \frac{b}{2a} \right)^2 - \frac{b^2}{4a^2} = -\frac{c}{a}. \] From here on, we can use the standard procedure for solving equations. We put all the constants on the right-hand side \[ \left(x + \frac{b}{2a} \right)^2 = -\frac{c}{a} + \frac{b^2}{4a^2}. \] Next we take the square root of both sides. Since the square function maps both positive and negative numbers to the same value, this step will give us two solutions: \[ x + \frac{b}{2a} = \pm \sqrt{ -\frac{c}{a} + \frac{b^2}{4a^2} }. \] Let's take a moment to cleanup the mess on the right-hand side a bit: \[ \sqrt{ -\frac{c}{a} + \frac{b^2}{4a^2} } = \sqrt{ -\frac{(4a)c}{(4a)a} + \frac{b^2}{4a^2} } = \sqrt{ \frac{- 4ac + b^2}{4a^2} } = \frac{\sqrt{b^2 -4ac} }{ 2a }. \]

Thus we have: \[ x + \frac{b}{2a} = \pm \frac{\sqrt{b^2 -4ac} }{ 2a }, \] which is just one step away from the final answer \[ x = \frac{-b}{2a} \pm \frac{\sqrt{b^2 -4ac} }{ 2a } = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 -4ac} }{ 2a }. \] This completes the proof.

Alternative proof of claim

To have a proof we don't necessarily need to show the derivation of the formula as we did. The claim was that $x_1$ and $x_2$ are solutions. To prove the claim we could have simply plugged $x_1$ and $x_2$ into the quadratic equation and verified that we get zero. Verify on your own.

Applications

The Golden Ratio

The golden ratio, usually denoted $\varphi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}=1.6180339\ldots$ is a very important proportion in geometry, art, aesthetics, biology and mysticism. It comes about from the solution to the quadratic equation \[ x^2 -x -1 = 0. \]

Using the quadratic formula we get the two solutions: \[ x_1 = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} = \varphi, \qquad x_2 = \frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2} = - \frac{1}{\varphi}. \]

You can learn more about the various contexts in which the golden ratio appears from the excellent wikipedia article on the subject. We will also see the golden ratio come up again several times in the remainder of the book.

Explanations

Multiple solutions

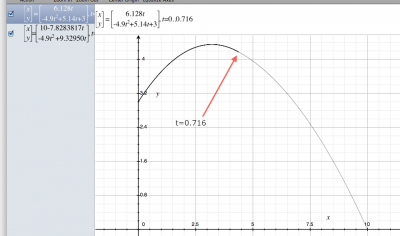

Often times, we are interested in only one of the two solutions to the quadratic equation. It will usually be obvious from the context of the problem which of the two solutions should be kept and which should be discarded. For example, the time of flight of a ball thrown in the air from a height of $3$ meters with an initial velocity of $12$ meters per second is obtained by solving a quadratic equation $0=(-4.9)t^2+12t+3$. The two solutions of the quadratic equation are $t_1=-0.229$ and $t_2=2.678$. The first answer $t_1$ corresponds to a time in the past so must be rejected as invalid. The correct answer is $t_2$. The ball will hit the ground after $t=2.678$ seconds.

Relation to factoring

In the previous section we discussed the quadratic factoring operation by which we could rewrite a quadratic function as the product of two terms $f(x)=ax^2+bx+c=(x-x_1)(x-x_2)$. The two numbers $x_1$ and $x_2$ are called the roots of the function: this is where the function $f(x)$ touches the $x$ axis.

Using the quadratic equation you now have the ability to factor any quadratic equation. Just use the quadratic formula to find the two solutions $x_1$ and $x_2$ and then you can rewrite the expression as $(x-x_1)(x-x_2)$.

Some quadratic expression cannot be factored, however. These correspond to quadratic functions whose graphs do not touch the $x$ axis. They have no solutions (no roots). There is a quick test you can use to check if a quadratic function $f(x)=ax^2+bx+c$ has roots (touches or crosses the $x$ axis) or doesn't have roots (never touches the $x$ axis). If $b^2-4ac>0$ then the function $f$ has two roots. If $b^2-4ac=0$, the function has only one root. This corresponds to the special case when the function touches the $x$ axis only at one point. If $b^2-4ac<0$, the function has no real roots. If you try to use the formula for finding the solutions, you will fail because taking the square root of a negative number is not allowed. Think about it—how could you square a number and obtain a negative number?

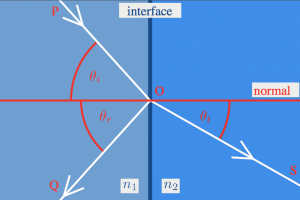

Trigonometry

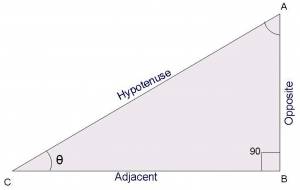

Put together any three lines and you get a triangle. In particular, if the triangle has one of its angles equal to $90^\circ$, we call this a right angle triangle.

In this section we are going to discuss right angle triangles in great detail and get used to their properties. You will learn how to use fancy Greek words like sinus, cosinus and tangent in order to refer to the various ratios of lengths in the triangle.

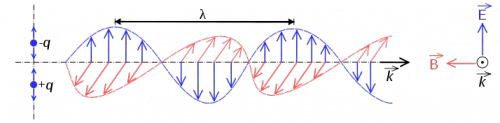

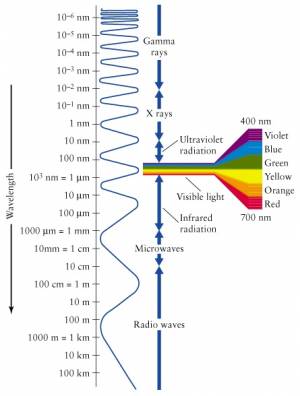

Understanding triangles and the trigonometric functions associated with them will be of fundamental importance for your later understanding of mathematics subjects like vectors and complex numbers and physics subjects like oscillations and waves.

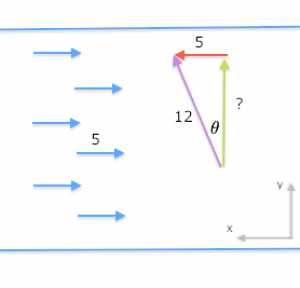

Concepts

- $A,B,C$: the three vertices of the triangle

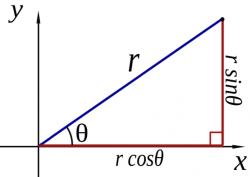

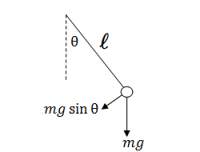

- $\theta$: the angle at the vertex $C$. Angles can be measured in degrees or radians.

- $\text{opp} \equiv \overline{AB}$: the length of the opposite side to $\theta$

- $\text{adj} \equiv \overline{BC}$: the length of side adjacent to $\theta$

- $\text{hyp} \equiv \overline{AC}$: the hypotenuse is longest side in the triangle

- $h$: the “height” of the triangle (in this case $h = \text{opp} = \overline{AB}$)

- $\sin\theta \equiv \frac{\text{opp}}{\text{hyp}}$: the sinus of theta, is the ratio of the lengths of the opposite side and the hypotenuse

- $\cos\theta \equiv \frac{\text{adj}}{\text{hyp}}$: the cosinus of theta, is the ratio of the adjacent and the hypotenuse lengths

- $\tan\theta \equiv \frac{\sin\theta}{\cos\theta} \equiv \frac{\text{opp}}{\text{adj}}$: the tangent is the ratio of the opposite divided by the adjacent

Pythagoras theorem

In a right angle triangle, the length of the hypotenuse squared is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other sides: \[ |\text{adj}|^2 + |\text{opp}|^2 = |\text{hyp}|^2. \]

If we divide both sides of the above equation by $|\text{hyp}|^2$ we obtain \[ \frac{|\text{adj}|^2}{ |\text{hyp}|^2 } + \frac{|\text{opp}|^2}{ |\text{hyp}|^2 } = 1, \] which can be rewritten as: \[ \cos^2\theta \ + \sin^2\theta = 1. \] This is a powerful trigonometric identity: a relationship between $\sin$ and $\cos$.

Sin and cos

Meet the trigonometric functions, or trigs for short. These are your new friends. Don't be shy now, say hello to them.

“Hello.”

“Hi.”

“Soooooo, you are like functions right?”

“Yep,” sin and cos reply in chorus.

“Okkkkkk, so what do you do?”

“Who me?”, asks cos, “well I tell the ratio.. Hmm..

wait, were you asking what I do as a function or specifically

what I do?”

“Both I guess?”

“Ok so as a function, I take angles as inputs and I give ratios as answers.

More specifically, I tell you how wide a triangle with that angle will be,”

says cos all in one breath.

“What do you mean wide?”, you ask.

“Oh yeah, I forgot to say, the triangle has to have hypotenuse of length 1.

So you see what happens is that, there is like a point $P$ that moves

around on a circle of radius 1, and we imagine a triangle that has

corners the origin, the point $P$ and the point on the $x$ axis that is

right below the point $P$.”

“I am not sure I get it,” you confess.

“Let me try to explain then”, says sin, “cos is always the one

to start off big and confuse people. I will start from zero.”

“OK. Sure. I mean I just don't see what circle cos is talking about.”

“Look on the next page, you will see a circle. The unit circle because

it has radius one. You see it yes?”

“Yes.”

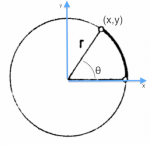

“The circle thing really cool. Imagine a point $P$ which stators from

the point $P(0)=(1,0)$ and moves in a circle of radius one.

The $x$ and $y$ coordinates of the point $P(\theta)=(P_x(\theta),\ P_y(\theta))$

as a function of $\theta$ are given by:

\[

P(\theta)=(P_x(\theta),\ P_y(\theta)) = (\cos\theta, \ \sin\theta ).

\]

So, either you think of us in the context of triangles

or you think of us in the context of the unit circle.”

“OK. Cool. I kind of get it,” you say it to keep conversation,

but in reality you are all weirded out. Talking functions?

“Well, thank you guys. It was nice to meet you, but you

know I have to get going now, so see you later,” you say to

get out the situation.

“OK. Peace out,” says sin, “anyways we are done here, since I told you the most important things.”

“See you later,” says cos.

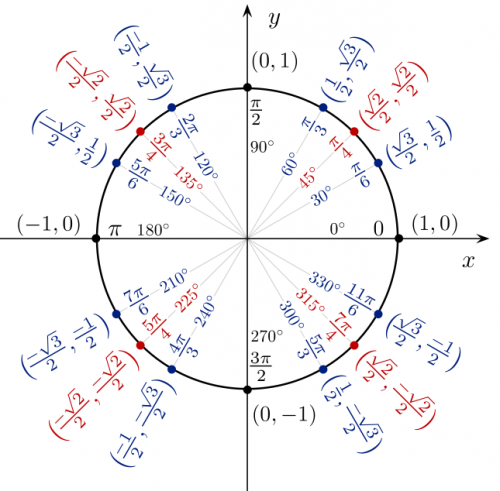

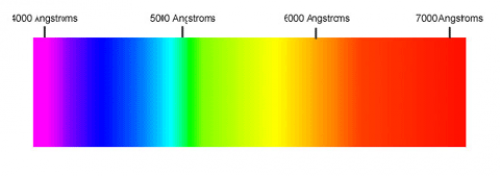

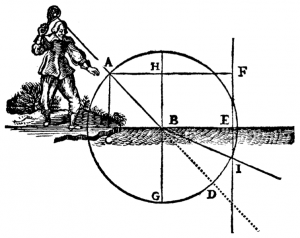

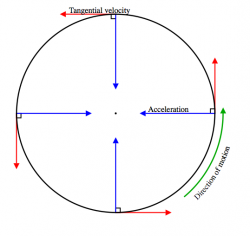

The unit circle

You should be familiar with the values of $\sin$ and $\cos$ for all the angles that are multiples of $\frac{\pi}{6}$ ($30^\circ$) or $\frac{\pi}{4}$ ($45^\circ$). All of them are shown in the diagram below. For each angle, the $x$ coordinate (the first number in the brackets below) is $\cos$ and the $y$ coordinate is $\sin$.

You might think that there is too much to remember. “Dude”, you say, “I was listening to your advice until now and learning, but now you are telling me to remember all those values with so many square roots in them. How am I to remember all of that?”

Actually, you just have to memorize one fact: \[ \sin(30^\circ) = \sin\!\!\left( \frac{\pi}{6} \right) = \frac{1}{2}. \]

My dad was like “You have to put this in the book”, and he is right. You can figure out all the other angles from this one. Let's start with $\cos(30^\circ)$. We know that the point $P$ on the unit circle at $30^\circ$ has vertical coordinate $\frac{1}{2}=\sin(30^\circ)$, and that by definition the horizontal component is the $\cos$ quantity we are looking for: \[ P = (\cos(30^\circ), \sin(30^\circ) ). \]

The key fact about the unit circle, is that all the points or it are at distance one from the centre. So knowing that $P$ is on the unit circle, and the value of $\sin(30^\circ)$, we can solve for $\cos(30^\circ)$. Indeed we start from the identity: \[ \cos^2\theta \ + \sin^2\theta = 1, \] which is true for all angles $\theta$. Moving things around, we obtain: \[ \cos(30^\circ) = \sqrt{ 1 - \sin^2(30^\circ) } = \sqrt{ 1 - \frac{1}{4} } = \sqrt{ \frac{3}{4} } = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}. \]

To get the values of $\cos(60^\circ)$ and $\sin(60^\circ)$, observe the symmetry of the circle. Sixty degrees measured from the $x$ axis, is the same as thirty degrees measured from the $y$ axis. So immediately you know that $\cos(60^\circ)=\sin(30^\circ)=\frac{1}{2}$. Therefore, it must be that $\sin(60^\circ) = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}$.

To get the values of sin and cos for angles that are multiples of $45^\circ$, we need to find the value $a$ such that \[ a^2 + a^2 = 1, \] since at $45^\circ$ both the horizontal part and the vertical part will be of the same length. The answer is obviously $a=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$, but because people don't like to see square roots in the denominator we have to write: \[ \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} = \cos(45^\circ) = \sin(45^\circ). \]

All of the other angles in the circle are just like the above three, but they have a negative sign in one or more of the components. Don't memorize them, but if you ever need one of their values draw a little circle and use the symmetry of the circle to find them. For example, $150^\circ$ is just like $30^\circ$, except the $x$ component is negative.

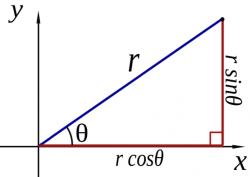

Non-unit circles

Consider now a point $Q(\theta)$ at an angle of $\theta$ on a circle of radius $R\neq1$. How can we find the $x$ and $y$ coordinates of the point $Q(\theta)$?

We saw that the coefficients $\cos\theta$ and $\sin\theta$ correspond the $x$ and $y$ coordinates of a point on the unit circle ($R=1)$. To obtain the coordinates for a point on a circle of radius $R$ we must scale the coordinates by a factor of $R$: \[ Q(\theta) = (Q_x(\theta), Q_y(\theta) ) = ( R\cos\theta, R\sin\theta ). \]

The take home message is that the functions $\cos\theta$ and $\sin\theta$

are generally useful for finding the “horizontal” and “vertical” components

of any length $r$.

The take home message is that the functions $\cos\theta$ and $\sin\theta$

are generally useful for finding the “horizontal” and “vertical” components

of any length $r$.

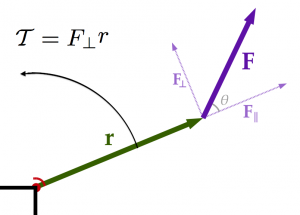

From this point on in the book, we will always talk about the length of the adjacent side as $r_x=r\cos\theta$ and the opposite side as $r_y = r\sin\theta$. It is extremely important that you get comfortable with this notation.

The reasoning behind the above calculations is as follows: \[ \begin{align*} \cos\theta \equiv \frac{\text{adj}}{\text{hyp}} = \frac{r_x}{r} & \quad \Rightarrow \quad r_x = r \cos\theta, \nl \sin\theta \equiv \frac{\text{opp}}{\text{hyp}}=\frac{r_y}{r} & \quad \Rightarrow \quad r_y = r\sin\theta. \end{align*} \]

Calculators

Make sure your calculator is set to the right units for angles. If you wanted to compute the sinus of 30 degrees what should you type into your calculator?

If you calculator is set to degrees then simply

type sin + 30 + =.

But what if your calculator is set to radians? You have two options:

- Change the

modeof the calculator so it works in degrees. - Convert $30^\circ$ to radians

\[ 30 \ [^\circ] \times \frac{ 2\pi \ [\text{rad}] }{ 360 \ [^\circ] } = \frac{\pi}{6} \ \text{[rad]}, \]

so you should type ''sin'' + $\pi$ + ''/'' + ''6'' + ''='' on your calculator.

Trigonometric identities

There is a number of important relationships between the values of the functions $\sin$ and $\cos$. These are known as trigonometric identities. There are three of them which you should memorize, and about a dozen others which are less important.

Formulas

The trigonometric functions are defined as \[ \cos(\theta)=x_P~~,~~\sin(\theta)=y_P~~,~~\tan(\theta)=\frac{y_P}{x_P}, \] where $P=(x_P,y_P)$ is a point on the unit circle.

The three identities that you must remember are:

1. Unit hypotenuse

\[ \sin^2(x)+\cos^2(x)=1. \] This is true by Pythagoras theorem and the definition of sin and cos. The ratios of the squares of the sides of a triangle is equal to the square of the size of the hypotenuse.

2. sico + sico

\[ \sin(a + b)=\sin(a)\cos(b) + \sin(b)\cos(a). \] The mnemonic for this one is “sico sico”.

3. coco - sisi

\[ \cos(a + b)=\cos(a)\cos(b) - \sin(a)\sin(b). \] The mnemonic for this one is “coco - sisi”—the negative sign is there because it is not good to be a sissy.

Derived formulas

If you remember the above thee formulas, you can derive pretty much all the other trigonometric identities.

Double angle formulas

Starting from the sico-sico identity above, and setting $a=b=x$ we can derive following identity: \[ \sin(2x) = 2\sin(x)\cos(x). \]

Starting from the coco-sisi identity, we derive: \[ \cos(2x) \ =\ 2\cos^2(x) - 1 \ = 2\left(1 - \sin^2(x)\right) - 1 = 1 - 2\sin^2(x), \] or if we rewrite to isolate the $\sin^2$ and $\cos^2$ we get: \[ \cos^2(x) = \frac{1}{2}\left(1+\cos(2x)\right), \qquad \sin^2(x) = \frac{1}{2}\left(1-\cos(2x)\right). \]

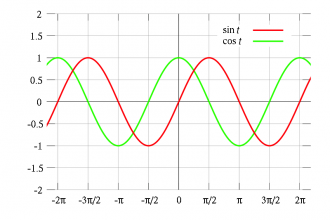

Self similarity

Sin and cos are periodic functions with period $2\pi$. So if we add multiples of $2\pi$ to the input, we get the same value: \[ \sin(x + 2\pi)=\sin(x +124\pi) = \sin(x), \qquad \cos(x+2\pi)=\cos(x). \]

Furthermore, sin and cos are self similar within each $2\pi$ cycle: \[ \sin(\pi-x)=\sin(x), \qquad \cos(\pi-x)=-\cos(x). \]

Sin is cos, cos is sin

Now it should come and no surprise if I tell you that actually sin and cos are just $\frac{\pi}{2}$-shifted versions of each other: \[ \cos(x)=\sin\!\left(x\!+\!\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=\sin\!\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\!-\!x\right), \ \ \sin\!\left(x\right) = \cos\left(x\!-\!\frac{\pi}{2}\right) = \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\!-\!x\right). \]

Sum formulas

\[ \sin\!\left(a\right)+\sin\!\left(b\right)=2\sin\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a+b)\right)\cos\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a-b)\right), \] \[ \sin\!\left(a\right)-\sin\!\left(b\right)=2\sin\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a-b)\right)\cos\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a+b)\right), \] \[ \cos\!\left(a\right)+\cos\!\left(b\right)=2\cos\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a+b)\right)\cos\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a-b)\right), \] \[ \cos\!\left(a\right)-\cos\!\left(b\right)=-2\sin\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a+b)\right)\sin\!\left(\frac{1}{2}(a-b)\right). \]

Product formulas

\[ \sin(a)\cos(b) = {1\over 2}(\sin{(a+b)}+\sin{(a-b)}), \] \[ \sin(a)\sin(b) = {1\over 2}(\cos{(a-b)}-\cos{(a+b)}), \] \[ \cos(a)\cos(b) = {1\over 2}(\cos{(a-b)}+\cos{(a+b)}). \]

Discussion

The above formulas will come in handy in many situations when you have to find some unknown in an equation or when you are trying to simplify a trigonometric expression. I am not saying you should necessarily memorize them, but you should be aware that they exist.

Geometry

Triangles

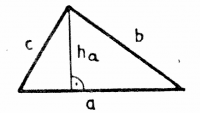

The area of a triangle is equal to $\frac{1}{2}$

times the length of the base times the height:

\[

A = \frac{1}{2} a h_a.

\]

Note that $h_a$ is the height of the triangle relative to the side $a$.

The area of a triangle is equal to $\frac{1}{2}$

times the length of the base times the height:

\[

A = \frac{1}{2} a h_a.

\]

Note that $h_a$ is the height of the triangle relative to the side $a$.

The perimeter of the triangle is: \[ P = a + b + c. \]

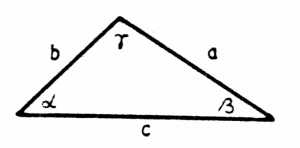

Consider now a triangle with internal angles $\alpha$, $\beta$ and $\gamma$. The sum of the inner angles in any triangle is equal to two right angles: $\alpha+\beta+\gamma=180^\circ$.

The sine law is:

\[

\frac{a}{\sin(\alpha)}=\frac{b}{\sin(\beta)}=\frac{c}{\sin(\gamma)},

\]

where $\alpha$ is the angle opposite to $a$, $\beta$ is the angle opposite to $b$ and $\gamma$ is the angle opposite to $c$.

The sine law is:

\[

\frac{a}{\sin(\alpha)}=\frac{b}{\sin(\beta)}=\frac{c}{\sin(\gamma)},

\]

where $\alpha$ is the angle opposite to $a$, $\beta$ is the angle opposite to $b$ and $\gamma$ is the angle opposite to $c$.

The cosine rules are: \[ \begin{align} a^2 & =b^2+c^2-2bc\cos(\alpha), \nl b^2 & =a^2+c^2-2ac\cos(\beta), \nl c^2 & =a^2+b^2-2ab\cos(\gamma). \end{align} \]

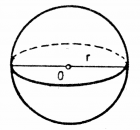

Sphere

A sphere is described by the equation \[ x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = r^2. \]

Surface area: \[ A = 4\pi r^2. \]

Volume: \[ V = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3. \]

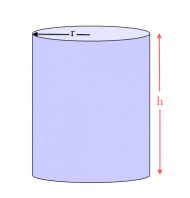

Cylinder

The surface area of a cylinder consists of the top and bottom circular surfaces plus the area of the side of the cylinder: \[ A = 2 \left( \pi r^2 \right) + (2\pi r) h. \]

The volume is given by product of the area of the base times the height of the cylinder: \[ V = \left(\pi r^2 \right)h. \]

Example

You open the hood of your car and see 2.0L written on top of the engine. The 2[L] refers to the total volume of the four pistons, which are cylindrical in shape. You look in the owner's manual and find out that the diameter of each piston (bore) is 87.5[mm] and the height of each piston (stroke) is 83.1[mm]. Verify that the total volume of the cylinder displacement of your engine is indeed 1998789[mm$^3$] $\approx 2$[L].

Links

[ A formula for calculating the distance between two points on a sphere ]

http://www.movable-type.co.uk/scripts/latlong.html

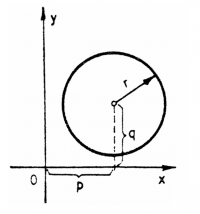

Circle

The circle is a set of points that are a constant distance from the centre. It is a very simple geometrical shape which comes up in many situations.

Definitions

- $r$: the radius of the circle

- $A$: the area of the circle

- $C$: the circumference of the circle

- $(x,y)$: is a point on the circle

- $\theta$: the angle (measured from the $x$-axis) of some point on the circle.

Formulas

The circle of radius $r$ centred at the origin is described by the following equation: \[ x^2 + y^2 = r^2. \] All points $(x,y)$ which satisfy this equation are part of the circle.

Instead of being centred at the origin, the

centre of the circle could be at any point in the plane $(p,q)$:

\[

(x-p)^2 + (y-q)^2 = r^2.

\]

Instead of being centred at the origin, the

centre of the circle could be at any point in the plane $(p,q)$:

\[

(x-p)^2 + (y-q)^2 = r^2.

\]

Explicit function

The equation of a circle is a relation or an implicit function involving $x$ and $y$. If we want an explicit function $f(x)$ for the circle, we can solve for $y$ to obtain: \[ y = \sqrt{ r^2 - x^2}, \quad -r \leq x \leq r, \] and \[ y = -\sqrt{ r^2 - x^2}, \quad -r \leq x \leq r. \] There are two functions, because a vertical line crosses that circle in two places. The first function corresponds to the top half of the circle and the second function corresponds to the bottom half.

Polar coordinates

Circles are such a common shape in mathematics that mathematicians developed a special “circular coordinate system” in order to describe them more easily.

It is possible to specify the coordinates $(x,y)$ of any point on the circle

in terms of the polar coordinates $r\angle\theta$, where $r$ measures the distance of

the point from the origin and $\theta$ is the angle measured from the $x$ axis.

It is possible to specify the coordinates $(x,y)$ of any point on the circle

in terms of the polar coordinates $r\angle\theta$, where $r$ measures the distance of

the point from the origin and $\theta$ is the angle measured from the $x$ axis.

To convert from the polar coordinates $r\angle\theta$ to the $(x,y)$ coordinates we use the trigonometric functions: \[ x = r\cos \theta, \qquad y = r\sin \theta. \]

Parametric equation

We can describe all the points on the circle in we specify a fixed radius $r$ and vary the angle $\theta$ over all angles: $\theta \in [0, 360^\circ)$. A parametric equation specifies the coordinates $(x(\theta), y(\theta))$ for the points on a curve for all values of the paramter $\theta$. The parametric equation for a circle of radius $r$ is given by: \[ \{ (x,y)\in\mathbb{R}^2 \ | \ x=r \cos\theta, y = r\sin\theta, \ \theta \in [0, 360^\circ) \}. \] You should try to visualize the curve traced by the point $(x(\theta),y(\theta))=(r\cos\theta,r\sin\theta)$ as $\theta$ varies from $0$ to $360^\circ$ and convince yourself that it traces out a circle of radius $r$.

If we let the parameter $\theta$ vary over a smaller interval, we will obtain subsets of the circle. For example, the parametric equation for the top half of the circle is: \[ \{ (x,y)\in\mathbb{R}^2 \ | \ x=r \cos\theta, y = r\sin\theta, \ \theta \in [0, 180^\circ] \}. \] The top half of the circle is also described by $\{ (x,y) \in\mathbb{R}^2 \ | \ y = \sqrt{ r^2 - x^2},\ x \in [-r,r] \}$, where the parameter used is the $x$ coordinate.

Area

The area of a circle of radius $r$ is given by \[ A = \pi r^2. \]

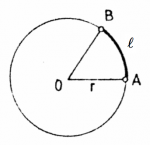

Circumference and arc length

The circumference of a circle is \[ C = 2 \pi r. \] This is the total length you would measure out if you were to follow the line of the circle.

What is the length of a part of the circle?

Say you have a piece of the circle, that corresponds

to the angle $\theta=30^\circ$. What is its length?

If the total length is $C=2 \pi r$ corresponds to

doing a full turn around the circle $360^\circ$, then

the arc length $\ell$ for a portion which corresponds to the angle $\theta$ is

\[

\ell = 2 \pi r \frac{\theta}{360}.

\]

We say that $\ell$ is the act length subtended by the angle $\theta$.

What is the length of a part of the circle?

Say you have a piece of the circle, that corresponds

to the angle $\theta=30^\circ$. What is its length?

If the total length is $C=2 \pi r$ corresponds to

doing a full turn around the circle $360^\circ$, then

the arc length $\ell$ for a portion which corresponds to the angle $\theta$ is

\[

\ell = 2 \pi r \frac{\theta}{360}.

\]

We say that $\ell$ is the act length subtended by the angle $\theta$.

Radians

Though degrees are a commonly used unit for angles, it is much better to measure angles in radians, which is the natural angle parameter. The conversion ratio is: \[ 2\pi \ \text{[radians]} = 360 \ \text{[degrees]}. \] For a circle of radius $r=1$, the arc length is equal to the angle in radians: \[ \ell = \theta_{radians}. \] Measuring radians is equivalent to measuring arc length on a circle of radius one.

Solving systems of linear equations

You know that to solve equations with one unknown like $2x + 4 = 7x$, you have to manipulate both sides of the equation until you isolate the unknown variable on one side. For the above equation we would subtract $2x$ from both sides to obtain: $4 = 5x$, which means that $x=\frac{4}{5}$.

What if you have two equations and two unknowns? For example: \[ \begin{align*} x + 2y & = 5, \nl 3x + 9y & = 21. \end{align*} \] Can you find values of $x$ and $y$ that satisfy these equations?

Concepts

- $x,y$: the two unknowns in the equations.

- $eq1, eq2$: a system of two equations that need to be solved simultaneously.

These equations will look like:

\[

\begin{align*}

a_1x + b_1y & = c_1, \nl

a_2x + b_2y & = c_2,

\end{align*}

\]

where the $a$s, $b$s and $c$s are given constants.

Principles

If you have $n$ equations and $n$ unknowns you can solve the equations simultaneously and find the values of the unknowns. There are different tricks which you can use to solve these equations simultaneously. We learn about three such tricks in this section.

Solution techniques

Solving by equating

We want to solve the following system of equations: \[ \begin{align*} x + 2y & = 5, \nl 3x + 9y & = 21. \end{align*} \]

We can isolate $x$ in both equations by moving all other variables and constants to the right sides of the equations: \[ \begin{align*} x & = 5 -2y, \nl x & = \frac{1}{3}(21 - 9y) = 7 - 3y. \end{align*} \]

The variable $x$ is still unknown, but we know two facts about it. We know that $x$ is equal to $5 - 2y$ and also that $x$ is equal to $7 - 3y$. So it must be that: \[ 5 - 2y = 7 -3y. \]

We can now solve for $y$ by adding $3y$ to both sides and subtracting $5$ from both sides to get $y = 2$.

We got $y=2$, but what is $x$? That is easy, we can plug in the value of $y$ that we found into any of the above equations. Say I pick the first one: \[ x = 5 - 2y = 5 - 2(2) = 1. \]

We are done, and $x=1,y=2$ is our solution.

Substitution

Let us go back to our set of equations: \[ \begin{align*} x + 2y & = 5, \nl 3x + 9y & = 21. \end{align*} \]

Looking at the first equation we can isolate $x$ to obtain: \[ \begin{align*} x & = 5 - 2y, \nl 3x + 9y & = 21. \end{align*} \]

If we substitute the top equation for $x$ into the bottom equation we will obtain: \[ 3(5-2y) + 9y = 21. \] We have just eliminated one of the unknowns by substitution. Let's do some massaging of this equation now. Expanding the bracket we get: \[ 15 - 6y +9y = 21, \] or \[ 3y = 6, \] which means that $y=2$. To get $x$, we use the original substitution $x = (5-2y)$ to get $x = (5-2(2)) = 1$.

Subtraction

There is a third way to solve the equations: \[ \begin{align*} x + 2y & = 5, \nl 3x + 9y & = 21. \end{align*} \]

Observe that we would not change the truth of any equation if we were to multiply it by some constant. For example, we can multiply the first equation by $3$ to obtain an equivalent set of equations: \[ \begin{align*} 3x + 6y & = 15, \nl 3x + 9y & = 21. \end{align*} \]

Why did I pick three as the multiplier? I chose this constant so that the first term (the $x$ term) now has the same coefficient in both equations.

If we subtract two true equations from each other we obtain another true equation. Let's do that. Let's subtract the top equation from the bottom one. We get: \[ 3x - 3x + 9y - 6y = 21 - 15 \quad \Rightarrow \quad 3y = 6. \] Did you see how the $3x$'s cancelled? That is why I originally chose to multiply the first equation by three. Now it is obvious that $y=2$, and substituting back into one of the original equations we have \[ x + 2(2) = 5, \] or moving the $2(2)=4$ to the other side we get $x=1$.

Discussion

These techniques can be extended to as many unknowns as you want. When we get to the chapter on linear algebra, we will learn a much more systematic way of solving this type of equations.

Introduction to physics

Introduction

One of the coolest things about understanding math is that you will automatically start to understand the laws of physics too. Indeed, most physics laws are expressed as mathematical equations. If you know how to manipulate equations and you know how to solve for the unknowns in them, then you know half of physics already.

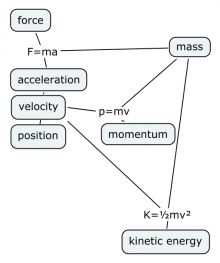

Ever since Newton figured out the whole $F=ma$ thing, people have used mechanics in order to achieve great technological feats like landing space ships on The Moon and recently even on Mars. You can be part of that too. Learning physics will give you the following superpowers:

- The power to predict the future motion of objects using equations.

It is possible to write down the equation which describes the position of

an object as a function of time $x(t)$ for most types of motion.

You can use this equation to predict the motion at all times $t$,

including the future.

"Yo G! Where's the particle going to be at when $t=1.3$[s]?",

you are asked. "It is going to be at $x(1.3)$[m] bro."

Simple as that. If you know the equation of motion $x(t)$,

which describes the position for //all// times $t$,

then you just have to plug $t=1.3$[s] into $x(t)$

to find where the object will be at that time.

- Special **physics vision** for seeing the world.

You will start to think in term of concepts like force, acceleration and velocity

and use these concepts to precisely describe all aspects of the motion of objects.

Without physics vision, when you throw a ball in the air you will see it go up,

reach the top, then fall down.

Not very exciting.

Now //with// physics vision,

you will see that at $t=0$[s] a ball is thrown into the $+\hat{y}$ direction

with an initial velocity of $\vec{v}_i=12\hat{y}$[m/s]. The ball reaches a maximum

height of $\max\{ y(t)\}= \frac{12^2}{2\times 9.81}=7.3$[m] at $t=12/9.81=1.22$[s],

and then falls back down to the ground after a total flight time of

$t_{f}=2\sqrt{\frac{2 \times 7.3}{9.81}}=2.44$[s].

Why learn physics?

A lot of knowledge buzz awaits you in learning about the concepts of physics and understanding how the concepts are connected. You will learn how to calculate the motion of objects, how to predict the outcomes of collisions, how to describe oscillations and many other things. Once you develop your physics skills, you will be able to use the equations of physics to derive one number (say the maximum height) from another number (say the initial velocity of the ball). Physics is a bit like playing LEGO with a bunch of cool scientific building blocks.

By learning how to solve equations and how to deal with complicated physics problems, you will develop your analytical skills. Later on, you can apply these skills to other areas of life; even if you do not go on to study science, the expertise you develop in solving physics problems will help you deal with complicated problems in general. Companies like to hire physicists even for positions unrelated to physics: they feel confident that if the candidate has managed to get through a physics degree then they can figure out all the business shit easily.

Intro to science

Perhaps the most important reason why you should learn physics is because it represents the golden standard for the scientific method. First of all, physics deals only with concrete things which can be measured. There are no feelings and zero subjectivity in physics. Physicists must derive mathematical models which accurately describe and predict the outcomes of experiments. Above all, we can test the validity of the physical models by running experiments and comparing the outcome predicted by the theory with what actually happens in the lab.

The key ingredient in scientific thinking is skepticism. The scientist has to convince his peers that his equation is true without a doubt. The peers shouldn't need to trust the scientist, but instead carry out their own tests to see if the equation accurately predicts what happens in the real world. For example, let's say that I claim that the equation of motion for the ball thrown up in the air with speed $12$[m/s] is given by $y_c(t)=\frac{1}{2}(-9.81)t^2 + 12t+0$. To test whether this equation is true, you can perform the throwing-the-ball-in-the-air experiment and record the maximum height the ball reaches and the total time of flight and compare them with those predicted by the claimed equation~$y_c(t)$. The maximum height that the ball will attain predicted by the claimed equation occurs at $t=1.22$ and is obtained by substituting this time into the equation of motion $\max_t\{ y_c(t)\}=y_{c}(1.22)=7.3$[m]. If this height matches what you measured in the real world, you can maybe start to trust my equation a little bit. You can also check whether the equation $y_c(t)$ correctly predicts the total time of flight which you measured to be $t=2.44$[s]. To do this you have to check whether $y_c(2.44) = 0$ as it should be when the ball hits the ground. If both predictions of the equation $y_c(t)$ match what happens in the lab, you can start to believe that the claimed equation of motion $y_c(t)$ really is a good model for the real world.

The scientific method depends on this interplay between experiment and theory. Theoreticians prove theorems and derive physics equations, while experimentalists test the validity of the equations. The equations that accurately predict the laws of nature are kept while inaccurate models are rejected.

Equations of physics

The best of the equations of physics are collected and explained in textbooks. Physics textbooks contain only equations that have been extensively tested and are believed to be true. Good physics textbooks also show how the equations are derived from first principles. This is really important, because it is much easier to remember a few general principles at the foundation of physics rather than a long list of formulas. Understanding trumps memorization any day of the week.

In the next section we learn about the equations $x(t)$, $v(t)$ and $a(t)$ which describes the motion of objects. We will also illustrate how the position equation $x(t)=\frac{1}{2}at^2 + v_it+x_i$ can be derived using simple mathematical methods (calculus). Technically speaking, you are not required to know how to derive the equations of physics—you just have to know how to use them. However, learning a bit of theory is a really good deal: reading a few extra pages of theory will give you a deep understanding of, not one, not two, but eight equations of physics.

Kinematics

Kinematics (from the Greek word kinema for motion) is the study of trajectories of moving objects. The equations of kinematics can be used to calculate how long a ball thrown upwards will stay in the air, or to calculate the acceleration needed to go from 0 to 100 km/h in 5 seconds. To carry out these calculations we need to know which equation of motion to use and the initial conditions (the initial position $x_i$ and the initial velocity $v_{i}$). Plug in the knowns into the equations of motion and then you can solve for the desired unknown using one or two simple algebra steps. This entire section boils down to three equations. It is all about the plug-number-into-equation technique.

The purpose of this section is to make sure that you know how to use the equations of motion and understand concepts like velocity and accretion well. You will also learn how to easily recognize which equation is appropriate need to use to solve any given physics problem.

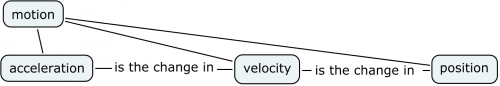

Concepts

The key notions used to describe the motion of an objects are:

- $t$: the time, measured in seconds [s].

- $x(t)$: the position of an object as a function of time—also known as the equation of motion. The position of an object is measured in metres [m].

- $v(t)$: the velocity of the object as a function of time. Measured in [m/s].

- $a(t)$: the acceleration of the object as a function of time. Measured in [m/s$^2$].

- $x_i=x(0), v_i=v(0)$: the initial (at $t=0$) position and velocity of the object (initial conditions).

Position, velocity and acceleration

The motion of an object is characterized by three functions: the position function $x(t)$, the velocity function $v(t)$ and the acceleration function $a(t)$. The functions $x(t)$, $v(t)$ and $a(t)$ are connected—they all describe different aspects of the same motion.

You are already familiar with these notions from your experience driving a car. The equation of motion $x(t)$ describes the position of the car as a function of time. The velocity describes the change in the position of the car, or mathematically \[ v(t) \equiv \text{rate of change in } x(t). \] If we measure $x$ in metres [m] and time $t$ in seconds [s], then the units of $v(t)$ will be metres per second [m/s]. For example, an object moving at a constant speed of $30$[m/s] will have its position change by $30$[m] each second.

The rate of change of the velocity is called the acceleration: \[ a(t) \equiv \text{rate of change in } v(t). \] Acceleration is measured in metres per second squared [m/s$^2$]. A constant positive acceleration means the velocity of the motion is steadily increasing, like when you press the gas pedal. A constant negative acceleration means the velocity is steadily decreasing, like when you press the brake pedal.

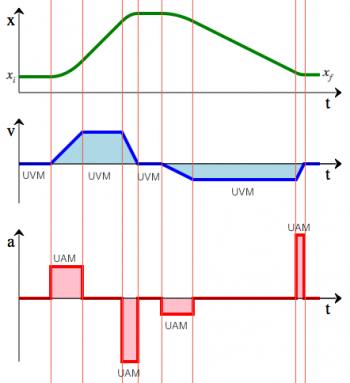

The illustration on the right shows the simultaneous graph of the

position, velocity and acceleration of a car during some time interval.

In a couple of paragraphs, we will discuss the exact mathematical equations which

describe $x(t)$, $v(t)$ and $a(t)$. But before we get to the math,

let us visually analyze the motion illustrated on the right.

The illustration on the right shows the simultaneous graph of the

position, velocity and acceleration of a car during some time interval.

In a couple of paragraphs, we will discuss the exact mathematical equations which

describe $x(t)$, $v(t)$ and $a(t)$. But before we get to the math,

let us visually analyze the motion illustrated on the right.

The car starts off with an initial position $x_i$ and just sits there for some time. The driver then floors the pedal to produce a maximum acceleration for some time, picks up speed and then releases the accelerator, but keeps it pressed enough to maintain a constant speed. Suddenly the driver sees a police vehicle in the distance and slams on the brakes (negative acceleration) and shortly afterwards brings the car to a stop. The driver waits for a few seconds to make sure the cops have passed. The car then accelerates backwards for a bit (reverse gear) and then maintains a constant backwards speed for an extended period of time. Note how “moving backwards” corresponds to negative velocity. In the end the driver slams on the brakes again to bring the car to a stop. The final position is $x_f$.

In the above example, we can observe two distinct types of motion. Motion at a constant velocity (uniform velocity motion, UVM) and motion with constant acceleration (uniform acceleration motion, UAM). Of course, there could be many other types of motion, but for the purpose of this section you are only responsible for these two.

- UVM: During times when there is no acceleration,

the car maintains a uniform velocity, that is,

$v(t)$ will be a constant function.

Constant velocity means that the position function

will be a line with a constant slope because, by definition, $v(t)= \text{slope of } x(t)$.

* UAM: During times where the car experiences a constant acceleration $a(t)=a$,

the velocity of the function will change at a constant rate.

The rate of change of the velocity is constant $a=\text{slope of } v(t)$,

so the velocity function must look like a line with slope $a$.

The position function $x(t)$ has a curved shape (quadratic) during moments of

constant acceleration.

Formulas

There are basically four equations that you need to know for this entire section. Together, these three equations fully describe all aspects of any motion with constant acceleration.

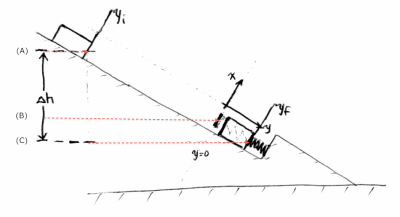

Uniform acceleration motion (UAM)

If the object undergoes a constant acceleration $a(t)=a$, like your car if you floor the accelerator, then its motion will be described by the following equations: \[ \begin{align*} x(t) &= \frac{1}{2}at^2 + v_i t + x_i, \nl v(t) &= at + v_i, \nl a(t) &= a, \end{align*} \] where $v_i$ is the initial velocity of the object and $x_i$ is its initial position.

There is also another useful equation to remember: \[ [v(t)]^2 = v_i^2 + 2a[x(t)- x_i], \] which is usually written \[ v_f^2 = v_i^2 + 2a\Delta x, \] where $v_f$ denotes the final velocity and $\Delta x$ denotes the change in the $x$ coordinate.

That is it. Memorize these equations, plug-in the right numbers, and you can solve any kinematics problem humanly imaginable. Chapter done.

Uniform velocity motion (UVM)

The special case where there is zero acceleration ($a=0$), is called uniform velocity motion or UVM. The velocity stays uniform (constant) because there is no acceleration. The following three equations describe the motion of the object under uniform velocity: \[ \begin{align} x(t) &= v_it + x_i, \nl v(t) &= v_i, \nl a(t) &= 0. \end{align} \] As you can see, these are really the same equations as in the UAM case above, but because $a=0$, some terms are missing.

Free fall

We say that an object is in free fall if the only force acting on it is the force of gravity. On the surface of the earth, the force of gravity produces a constant acceleration of $a=-9.81$[m/s$^2$]. The negative sign is there because the gravitational acceleration is directed downwards, and we assume that the $y$ axis points upwards. The motion of an object in free fall is described by the UAM equations.

Examples

We will now illustrate how the equations of kinematics are used to solve physics problems.

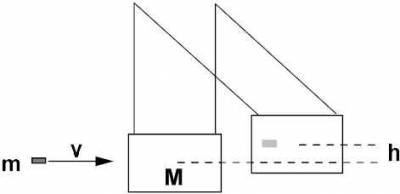

Moroccan example

Suppose your friend wants to send you a ball wrapped in aluminum foil from his balcony, which is located at a height of $x_i=44.145$[m]. How long does it take for the ball to hit the ground?

We recognize that this is a problem with acceleration, so we start by writing out the general UAM equations: \[ \begin{align*} y(t) &= \frac{1}{2}at^2 + v_i t + y_i, \nl v(t) &= at + v_i. \end{align*} \] To find the answer, we substitute the known values $y(0)=y_i=44.145$[m], $a=-9.81$ and $v_i=0$[m/s] (since the ball was released from rest) and solve for $t_{fall}$ in the equation $y(t_{fall}) = 0$ since we are interested in the time when the ball will reach a heigh of zero. The equation is \[ y(t_{fall}) = 0 = \frac{1}{2}(-9.81)(t_{fall})^2+0(t_{fall}) + 44.145, \] which has solution $t_{fall} = \sqrt{\frac{44.145\times 2}{9.81}}= 3$[s].

0 to 100 in 5 seconds

Suppose you want to be able to go from $0$ to $100$[km/h] in $5$ seconds with your car. How much acceleration does your engine need to produce, assuming it produces a constant amount of acceleration.

We can calculate the necessary $a$ by plugging the required values into the velocity equation for UAM: \[ v(t) = at + v_i. \] Before we get to that, we need to convert the velocity in [km/h] to velocity in [m/s]: $100$[km/h] $=\frac{100 [\textrm{km}]}{1 [\textrm{h}]} \cdot\frac{1000[\textrm{m}]}{1[\textrm{km}]} \cdot\frac{1[\textrm{h}]}{3600[\textrm{s}]}$= 27.8 [m/s]. We fill in the equation with all the desired values $v(5)=27.8$[m/s], $v_i=0$, and $t=5$[s] and solve for $a$: \[ v(5) = 27.8 = a(5) + 0. \] We conclude that your engine has to produce a constant acceleration of $a=5.56$[m/s$^2$] or more.

Moroccan example II

Some time later, your friend wants to send you another aluminum ball from his apartment located on the 14th floor (height of $44.145$[m]). In order to decrease the time of flight, he throws the ball straight down with an initial velocity of $10$[m/s]. How long does it take before the ball hits the ground?

Imagine the building with the $y$ axis measuring distance upwards starting from the ground floor. We know that the balcony is located at a height of $y_i=44.145$[m], and that at $t=0$[s] the ball starts with $v_i=-10$[m/s]. The initial velocity is negative, because it points in the opposite direction to the $y$ axis. We know that there is an acceleration due to gravity of $a_y=-g=-9.81$[m/s$^2$].

We start by writing out the general UAM equation: \[ y(t) = \frac{1}{2}a_yt^2 + v_i t + y_i. \] We want to find the time when the ball will hit the ground, so $y(t)=0$. To find $t$, we plug in all the known values into the general equation: \[ y(t) = 0 = \frac{1}{2}(-9.81)t^2 -10 t + 44.145, \] which is a quadratic equation in $t$. First rewrite the quadratic equation into the standard form: \[ 0 = \underbrace{4.905}_a t^2 + \underbrace{10.0}_b \ t - \underbrace{44.145}_c, \] and then solve using the quadratic equation: \[ t_{fall} = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{ b^2 - 4ac }}{2a} = \frac{-10 \pm \sqrt{ 25 + 866.12}}{9.81} = 2.53 \text{ [s]}. \] We ignored the negative-time solution because it corresponds to a time in the past. Comparing with the first Moroccan example, we see that the answer makes sense—throwing a ball downwards will make it fall to the ground faster than just dropping it.

Discussion

Most kinematics problems you will be asked to solve follow the same pattern as the above examples. You will be given some of the initial values and asked to solve some unknown quantity. It is important to keep in mind the signs of the numbers you plug into the equations. You should always draw the coordinate system and indicate clearly (to yourself) the $x$ axis which measures the displacement. If a velocity or acceleration quantity points in the same direction as the $x$ axis then it is a positive number while quantities that point in the opposite direction are negative numbers.

All this talk of $v(t)$ being the “rate of change of $x(t)$” is starting to get on my nerves. The expression “rate of change of” is an euphemism for the calculus term derivative. We will now take a short excursion into the land of calculus in order to define some basic concepts (derivatives and integrals) so that we can use us this more precise terminology in the remainder of the book.

Introduction to calculus

Calculus is the study of functions. We use calculus in order to describe how quantities change over time (derivatives $\frac{d}{dt}$) or to find the total amount of quantities that vary over time (integration $\int\cdot\;dt$).

Derivatives

The derivative function $f'(t)$ is a description of how the function $f(t)$ changes over time. The derivative encodes the information about rate of change or the slope of the function $f(t)$: \[ f'(t) \equiv \text{slope}_f(t) = \frac{ \text{change in} \ f(t) }{ \text{change in}\ t } = \frac{ f(t+\Delta t) - f(t) }{ \Delta t }. \] If the slope of $f(t)$ is big at some value of $t$, this means that the function changes very quickly at that time. At the other extreme we have the points where $f'(t)=0$ which correspond to locations where the function is flat—it is neither increasing nor decreasing.

Derivatives are used widely in many areas of science, so there are many names and symbols used to denote this operation: $Df(t) = f'(t)=\frac{df}{dt}=\frac{d}{dt}\!\left\{ f(t) \right\}=\dot{f}$. You shouldn't think of $f'(t)$ as a separate entity from $f(t)$, but as a property of the function $f(t)$. Indeed, it is best to think of the derivative as an operator $\frac{d}{dt}$ which can be applied to any function in order to obtain the slope information.

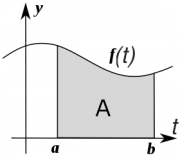

Integrals

An integral corresponds to the computation of an area

under a curve $f(t)$ between two points:

\[

A(a,b) \equiv \int_{t=a}^{t=b} f(t)\;dt.

\]

The symbol $\int$ is a mnemonic for sum,

since the area under the curve corresponds in some

sense to the sum of the values of the function $f(t)$

between $t=a$ and $t=b$.

The integral is the total amount of $f$ between $a$ and $b$.

An integral corresponds to the computation of an area

under a curve $f(t)$ between two points:

\[

A(a,b) \equiv \int_{t=a}^{t=b} f(t)\;dt.

\]

The symbol $\int$ is a mnemonic for sum,

since the area under the curve corresponds in some

sense to the sum of the values of the function $f(t)$

between $t=a$ and $t=b$.

The integral is the total amount of $f$ between $a$ and $b$.

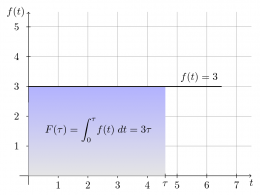

Example 1

We can easily find the area under the constant function $f(t) = 3$

between any two points because the region under the curve is rectangular.

We choose to use $t=0$ as the reference point and compute

the indefinite integral $F(\tau)$ which corresponds to the

area under $f(t)$ starting from $t=0$ and going until $t=\tau$:

\[

F(\tau) \equiv A(0,\tau) = \! \int_0^\tau \!\! f(t)\;dt = 3 \tau.

\]

Indeed the area is equal to the height times the length of the rectangle.

We can easily find the area under the constant function $f(t) = 3$

between any two points because the region under the curve is rectangular.

We choose to use $t=0$ as the reference point and compute

the indefinite integral $F(\tau)$ which corresponds to the

area under $f(t)$ starting from $t=0$ and going until $t=\tau$:

\[

F(\tau) \equiv A(0,\tau) = \! \int_0^\tau \!\! f(t)\;dt = 3 \tau.

\]

Indeed the area is equal to the height times the length of the rectangle.

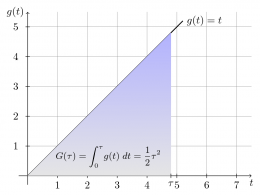

Example 2

We can also easily compute the area under the line $g(t)=t$

since the region under the curve is triangular.

Recall that the area of a triangle is given by the length of

the base times the height divided by two.

We can also easily compute the area under the line $g(t)=t$

since the region under the curve is triangular.

Recall that the area of a triangle is given by the length of

the base times the height divided by two.

We choose $t=0$ as our starting point again and find the area: \[ G(\tau) \equiv A(0,\tau) = \int_0^\tau g(t) \; dt = \frac{\tau\times\tau}{2} = \frac{1}{2}\tau^2. \]

We were able to compute the above integrals thanks to the simple geometry of the areas under the curves. Later on in this book we will develop techniques for finding integrals of more complicated functions. In fact, there is an entire course, Calculus II, which is dedicated to the task of finding integrals.

What I need you to remember for now is that the integral of a function gives you the area under the curve, which is in some sense the total amount of the function accumulated during that period.

You should also remember the following two formulas: \[ \int_0^\tau a \;dt = a\tau, \qquad \int_0^\tau at \;dt = \frac{1}{2}a\tau^2. \] The second formula is a generalization of the formula we saw in Example 2.

Using the above formulas in combination, you can now compute the integral under an arbitrary line $h(t)=mt+b$ as follows: \[ H(\tau)= \int_0^\tau h(t)\;dt = \int_0^\tau (mt + b)\;dt = \int_0^\tau \!mt\;dt\ + \int_0^\tau \!b\;dt = \frac{1}{2}m\tau^2 + b \tau. \]

Why do we need integrals? How often do you need to compute the area below a function $f(t)$ in the real life?

Inverse operations

The integral is the inverse operation of the derivative. You are already familiar with the inverse relationship between functions. When solving equations, we use inverse functions to undo the effects of functions that stand in the way. Similarly, we use the integral operation to undo the effects of the derivative operation. For example, if you want to find the function $f(t)$ in an equation of the form \[ \frac{d}{dt} \left\{ f(t) \right\} = g(t), \] you have to apply the integration operation on both sides of the equation. The integral operation will undo the derivative operation on the left so we will obtain: \[ \int \frac{d}{dt} \left\{ f(t) \right\} \;dt = f(t) = \int g(t) \; dt. \]

From now on, every time you want to undo a derivative, you can apply the integral operation: \[ \text{int}\!\left( \text{diff}( f(x) ) \right) = \int_0^x \left( \frac{d}{dt} f(t) \right) \; dt = \int_0^x \! f'(t) \; dt = f(x) + C. \] Note that integration always introduces an additive constant term $+C$. This is because the derivative operation destroys the information about the initial value of the function. The functions $f(x)+1$ and $f(x)+2$ have same derivative $f'(x)$ so when we solve the inverse problem of finding $f(x)$ from $f'(x)$, we must state our answer as $f(x)+C$ for some constant $C$.

Banking example

In order to illustrate how derivative and integral operations can be used in the real world, we will draw an analogy with a scenario that every student is familiar with. Consider the function $\textrm{ba}(t)$ which represents your bank account balance at time $t$, and the function $\textrm{tr}(t)$ which corresponds to the transactions (deposits and withdraws) on your account.

The function $\textrm{tr}(t)$ is the derivative of the function $\textrm{ba}(t)$. Indeed, if you ask “how does my balance change over time”, the answer will be the function $\textrm{tr}(t)$. Using the mathematical symbols, we can represent this relationship as follows: \[ \textrm{tr}(t) = \frac{d}{dt} \left\{ \textrm{ba}(t) \right\}. \] If the derivative is big (and negative), your account balance will be depleted quickly.

Suppose now, that you have the record of all the transactions on your account $\textrm{tr}(t)$ and you want to compute the final account balance at the end of the month. Since $\textrm{tr}(t)$ is the derivative of $\textrm{ba}(t)$, you can use an integral (the inverse operation to the derivative) in order to obtain $\textrm{ba}(t)$. Knowing the balance of your account at the beginning of the month, you can calculate the balance at the end of the month by calculating the following integral: \[ \textrm{ba}(30)=\textrm{ba}(0)+\int_0^{30} \textrm{tr}(t)\:dt. \] This calculation makes sense intuitively since $\textrm{tr}(t)$ represents the instantaneous change in $\textrm{ba}(t)$. If you want to find the overall change from day 0 until day 30, you need to compute the total of all the changes on the account. More generally, the integrals are used every time you need to calculate the total of some quantity over a time period.

In the next section we will see how the integration techniques learned in this section can be applied to the subject of kinematics. We will see how the equations of motion for UAM are derived from first principles.

Kinematics with calculus

To carry out kinematics calculations, all we need to do is plug the initial conditions into the correct equation of motion and then read out the answer. It is all about the plug-number-into-equation skill. But where do the equations of motion come from? Now that you know a little bit of calculus, you can see how the equations of motion are derived.

Concepts

Recall the concepts related to the motion of objects (kinematics):

- $t$: the time, measured in seconds [s].

- $x(t)$: the position as a function of time, also known as the equation of motion.

- $v(t)$: the velocity.

- $a(t)$: the acceleration.

- $x_i=x(0), v_i=v(0)$: the initial conditions.

Position, velocity and acceleration revisited

Recall that the purpose of the equations of kinematics is to predict the motion of objects. Suppose that you know the acceleration of the object $a(t)$ at all times $t$. How could you find $x(t)$ starting from $a(t)$?

The equations of motion $x(t)$, $v(t)$ and $a(t)$ are related: \[ a(t) \overset{\frac{d}{dt} }{\longleftarrow} v(t) \overset{\frac{d}{dt} }{\longleftarrow} x(t). \] The velocity is the derivative of the position function and the acceleration is the derivative of the velocity.

General procedure

If you know the acceleration of an object $a(t)$ as a function of time and its initial velocity $v_i=v(0)$, you can find its velocity $v(t)$ function at all later times. This is because the acceleration function $a(t)$ describes the change in the velocity of the object. If you know that the object started with an initial velocity of $v_i \equiv v(0)$, the velocity at a later time $t=\tau$ is equal to $v_i$ plus the total acceleration of the object between $t=0$ and $t=\tau$: \[ v(\tau)=v_i+\int_0^\tau a(t)\;dt. \]

If you know the initial position $x_i$ and the velocity function $v(t)$ you can find the position function $x(t)$ by using integration again. We find the position at time $t=\tau$ by adding up all the velocity (changes in the position) that occurred between $t=0$ and $t=\tau$: \[ x(\tau) = x_i + \int_0^\tau v(t)\:dt. \]

The procedure for finding $x(t)$ starting from $a(t)$ can be summarized as follows: \[ a(t) \ \ \overset{v_i + \int\!dt}{\longrightarrow} \ \ v(t) \ \ \overset{x_i+ \int\!dt }{\longrightarrow} \ \ x(t). \]

We will now illustrate how to apply this procedure for the important special case of motion with constant acceleration.

Derivation of the UAM equations of motion

Consider an object undergoing uniform acceleration motion (UAM) with acceleration function $a(t) =a$. Suppose that we know the initial velocity of $v_i \equiv v(0)$, and you want to find the velocity at later time $t=\tau$. We have to compute the following integral: \[ v(\tau) =v_i+ \int_0^\tau a(t)\;dt = v_i + \int_0^\tau a \ dt = v_i + a\tau. \] The velocity as a function of time is given by the initial velocity $v_i$ plus the integral of the acceleration.

If you know the initial position $x_i$ and the velocity function $v(t)$ you can find the position function $x(t)$ by using integration again. The formula is \[ x(\tau) = x_i + \int_0^\tau v(t)\:dt = x_i + \int_0^\tau (at+v_i) \; dt = x_i + \frac{1}{2}a\tau^2 + v_i\tau. \]

Note that the above calculations required the knowledge of the initial conditions $x_i$ and $v_i$. This is because the integral calculations tell us the change in the quantities relative to their initial values.

The fourth equation

The fourth equation of motion \[ v_f^2 = v_i^2 + 2a(x_f-x_i) \] can be derived by combining the equations of motion $v(t)$ and $x(t)$.

Consider squaring both sides of the velocity equation $v_f = v_i + at$ to obtain \[ v_f^2 = (v_i + at)^2 = v_i^2 + 2av_it + a^2t^2 = v_i^2 + 2a(v_it + \frac{1}{2}at^2). \] We can recognize the term in the bracket is equal to $\Delta x = x(t)-x_i=x_f-x_i$.

Discussion

Forces are the causes of acceleration

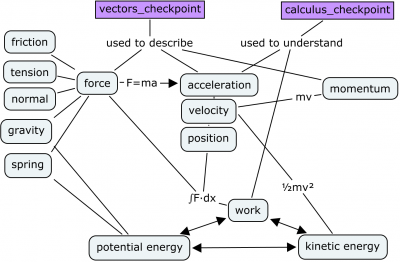

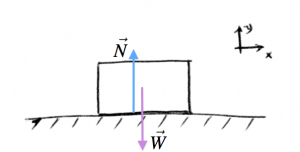

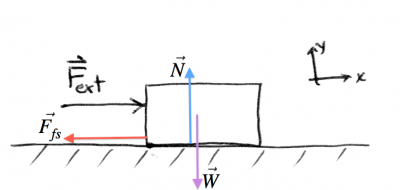

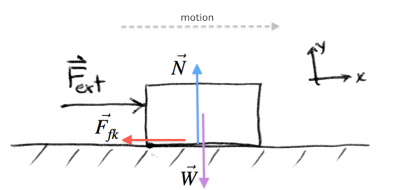

According to Newton's second law of motion, forces are the cause of acceleration and the formula that governs this relationship is \[ F_{net}=ma, \] where $F_{net}$ is the magnitude of the net force on the object.

In a later chapter, we will learn about dynamics which is the study of the different kinds of forces that can act on objects: the gravitational force $\vec{F}_g$, the spring force $\vec{F}_s$, the friction force $\vec{F}_f$, the electric force $\vec{F}_e$, the magnetic force $\vec{F}_b$ and many others. To find the acceleration on an object we must add together (as vectors) all of the forces which are acting on the object and divide by the mass \[ \sum \vec{F} = F_{net}, \qquad \Rightarrow \qquad a = \frac{1}{m} F_{net}. \]

The physics procedure for predicting the motion of objects can be summarized as follows: \[ \frac{1}{m} \underbrace{ \left( \sum \vec{F} = \vec{F}_{net} \right) }_{\text{dynamics}} = \underbrace{ a(t) \ \overset{v_i+ \int\!dt }{\longrightarrow} \ v(t) \ \overset{x_i+ \int\!dt }{\longrightarrow} \ x(t) }_{\text{kinematics}}. \]

Free fall revisited

The force of gravity on a object of mass $m$ on the surface of the earth is given by $\vec{F}_g=-mg\hat{y}$, where $g=9.81$[m/s$^2$] is the gravitational constant. Recall that we said that an object is in free fall when the only force acting on it is the force of gravity. In this case, Newton's second law tells us that \[ \begin{align*} \vec{F}_{net} &= m\vec{a} \nl -mg\hat{y} &= m\vec{a}. \end{align*} \] Dividing both sides by the mass we see that the acceleration of an object in free fall is $\vec{a} = -9.81\hat{y}$.

It is interesting to note that the mass of the object does

not affect its acceleration during free fall.

The force of gravity is proportional to the mass of the object,

but the acceleration is inversely proportional to the mass of the object

so overall we get $a_y = -g$ for objects in free fall regardless of their mass.

This observation was first made by Galileo in his famous Leaning Tower of Pisa experiment

during which he dropped a wooden ball and a metal ball (of same shape but different mass)

from the Leaning Tower of Pisa and observed that they fall to the ground in the same time.

Search for “Apollo 15 feather and hammer drop” on YouTube to see a similar experiment

performed on The Moon.

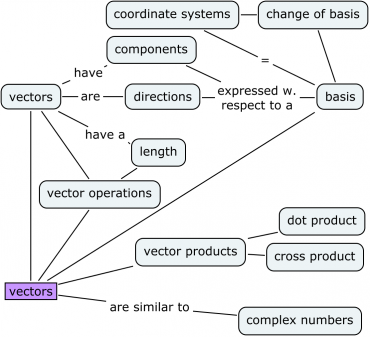

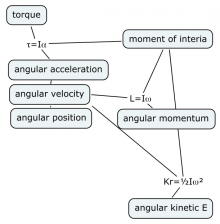

What next?